Source: Library of Congress. This image is in the public domain.

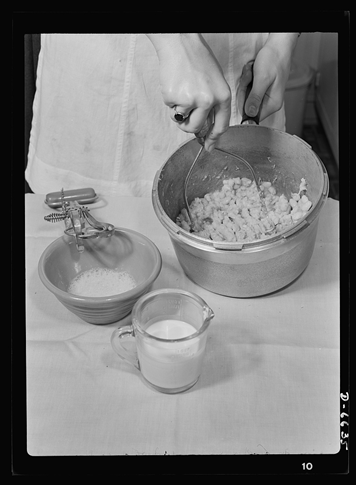

“’Share The Meat’ recipes. Baked bean loaf. Mash three cups of cooked beans, or chop them very fine. Add a chopped onion, one-half cup of milk (water or the liquid from the cooked beans may be substituted), a beaten egg and a cup of bread crumbs. A little finely chopped celery is good too. Season to taste with salt, pepper and dried herbs.” 1942

What’s new?

The June 19-25 issue of the magazine New Scientist has a cover story titled “The Algorithms That Run Your Life. What they do, and how they shape your every decision.” The article discusses the use of computers in Facebook’s news feed, weather forecasting, compression of computer files to take up less space, Google search, financial trading, encryption, medical decision making, Internet communication, and computer simulation.

What does it mean?

In a sidebar, New Scientist discusses the meaning of algorithm, defining it first as “a sequence of instructions that takes an input, performs some repeatable computation on it and provides an output” or “a super-precise recipe.” But the author also notes that increasingly the word algorithm is used “to describe almost anything that a computer accomplishes.”

The examples discussed in the article, and even the discussion of the word algorithm, conflate a lot of issues with the increasing use of computers. One issue is the way in which the algorithm is created; it can be based on an understanding of the context, as in weather forecasting, or it can be based on vast amounts of data resulting in an algorithm that no one really understands, as in the Facebook algorithm. Other issues are the degree to which the algorithm functions with or without human supervision, the magnitude of the potential ill effects if the algorithm errs in a particular case, and the awareness of users of how the algorithm was created and is being used.

In the editorial comment in the issue, New Scientist highlights that last issue: “We outsource all kinds of decisions to computers, yet can’t easily see how these were made.” They cite the recent use in England of an algorithm to assign grades to students who had missed taking exams during the pandemic and the resulting problems.

The New Scientist article is valuable in the wide range of examples it cites, prompting me to search for other algorithms in my life. For example, I mostly use my point-and-shoot Nikon Coolpix camera in its automatic mode, which surely affects the quality of the pictures I take without my thinking about it too much. As I seek to improve my photographs, I will need to abandon my reliance on the camera’s algorithm and make conscious choices of settings.

I have had to learn to drive differently in my partner’s 2018 Kia with automatic transmission than in my own 2010 Kia with manual transmission. The former decides when to shift while I must make that decision myself in my car, but I find I sometimes need to think and anticipate the automatic action of Mark’s car (for example, when merging on the highway).

I use Google for directions from one place to another, sometimes even in my own town, and usually I look at what its algorithm for finding the shortest route suggests, then I decide the suggestion is good and I follow it, but in some cases, I know that the route will not be a good one (school is letting out right now so that route will be slow). I appreciate the suggestion from the algorithm but stay in complete control

More disconcerting were the examples where I know there is an algorithm, but I really don’t understand what it is doing. Some pieces of software (Zoom, Word, or Facebook) take actions that I simply can’t explain, replicate, or avoid. I know that some online stores adjust the price they show me based on whether I am logged in or not and on whether I enter a catalog number from which I am shopping. Savvy travelers try to time their purchase of, for example, airline tickets – but I really don’t want to spend my time trying to outwit an algorithm. The clock across the room from me is an atomic clock, so checks its time with a central location, but sometimes, inexplicably to me, it suddenly speeds ahead in time, eventually reaching what it must have determined is the correct time. What algorithms can you find in your life?

What does it mean for you?

Highly automated manufacturing machines depend on many algorithms, most of which improve the operation of that manufacturing facility, but I urge you to look under the hood of those algorithms. An algorithm that is predicting tool wear and telling an operator when to replace a tool may or may not be tuned to the priorities and costs of your shop. An algorithm that is pricing out items and estimating time to create a bid may or may not reflect your changing costs and your workforce’s capabilities. In some cases, what is optimal for an algorithm when viewed at a small scale, may not be optimal when viewed in the context of your entire system.

We can’t, of course, look into every algorithm in our businesses, if only because companies treat such knowledge as proprietary. If I don’t create the algorithm, or I don’t have enough knowledge of the algorithm to let me adjust to it, then I have to act based on trust. The New Scientist editorial concludes with the sentence, “But who knows where we will end up if we carry on delegating decisions to machines we can’t completely understand?”

Ultimately, I believe, the factor that matters most is trust, but not trust of the machine, but trust of the people who programmed that machine. Do I trust the people and the company that made that algorithm? There are online stores I no longer use because I cannot trust that they are showing me a fair price for an item; I don’t want to buy from a company that is trying to game me.

Business has always, of course, relied on trust, but the complicated an often hidden nature of algorithms complicates the evaluation. Who are you going to trust?

Where can I learn more?

In 2017 The Deseret News published a similar article with other examples of algorithms, including the evaluation of teachers, and with a discussion of possible impacts on society. A 2018 article in Wired documented a week of following the suggestions of algorithms. The author concludes that the everyday algorithms of Facebook, Spotify, and Amazon probably don’t affect her as much as the algorithms that are more hidden: “When algorithms decide if we should be put forward for that job or be offered that loan, or inform which new train routes get built or whether our legal cases get dropped or pursued, we don’t get a say.”

An article on machine learning has some very good examples of how algorithms affect our lives, such as spam filters in our email. The Pew Research Center has studied the possible effects of increasing use of algorithms.

This list of algorithms in manufacturing may help you identify the algorithms in manufacturing you are using, or perhaps should be using. Industry 4.0 has a heavy emphasis on smart manufacturing, often implemented through computer algorithms.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.